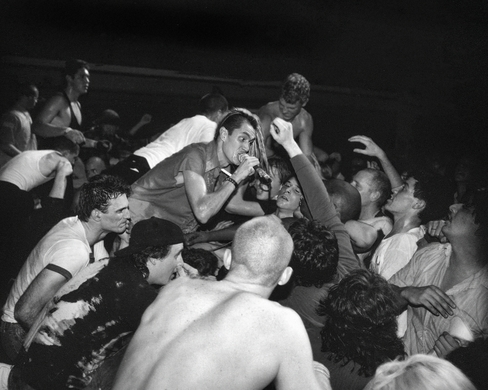

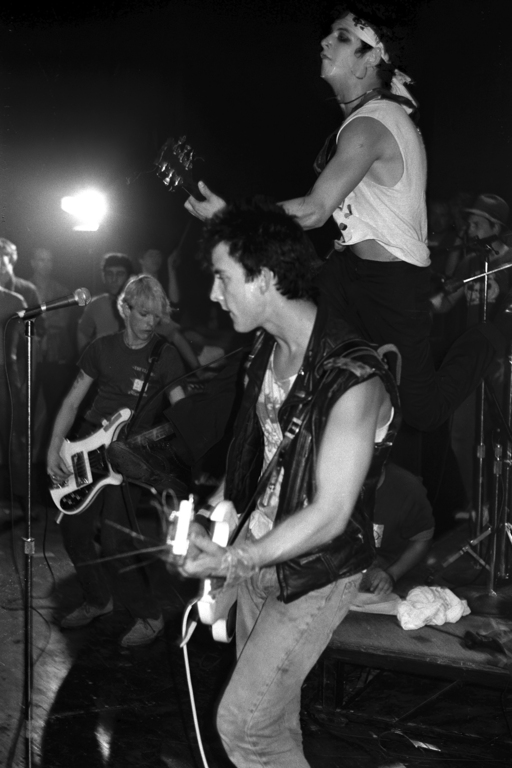

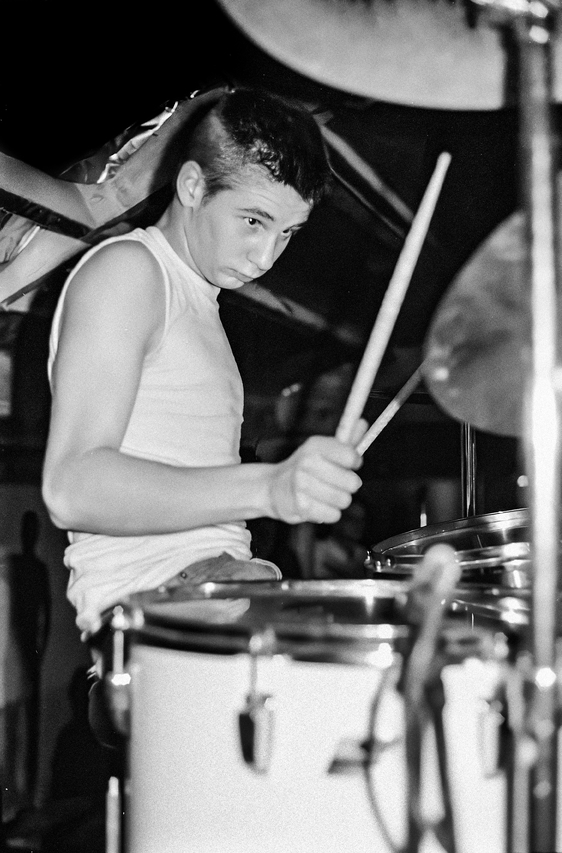

Carrying a camera into punk clubs was an extension of what I wanted to do: observe, document, & preserve. Over time, that evolved into an ethos of authenticity – I never wanted to stage or sanitize what I saw. Sweaty basement shows or stadium gigs, my goal has always been the same: to capture the truth of the moment, without interference.

That mindset has stayed with me: be present, stay grounded, don’t chase trends, and always respect what you’re documenting. Punk shaped my perspective, but my foundation came from home – from my father, my mentor.

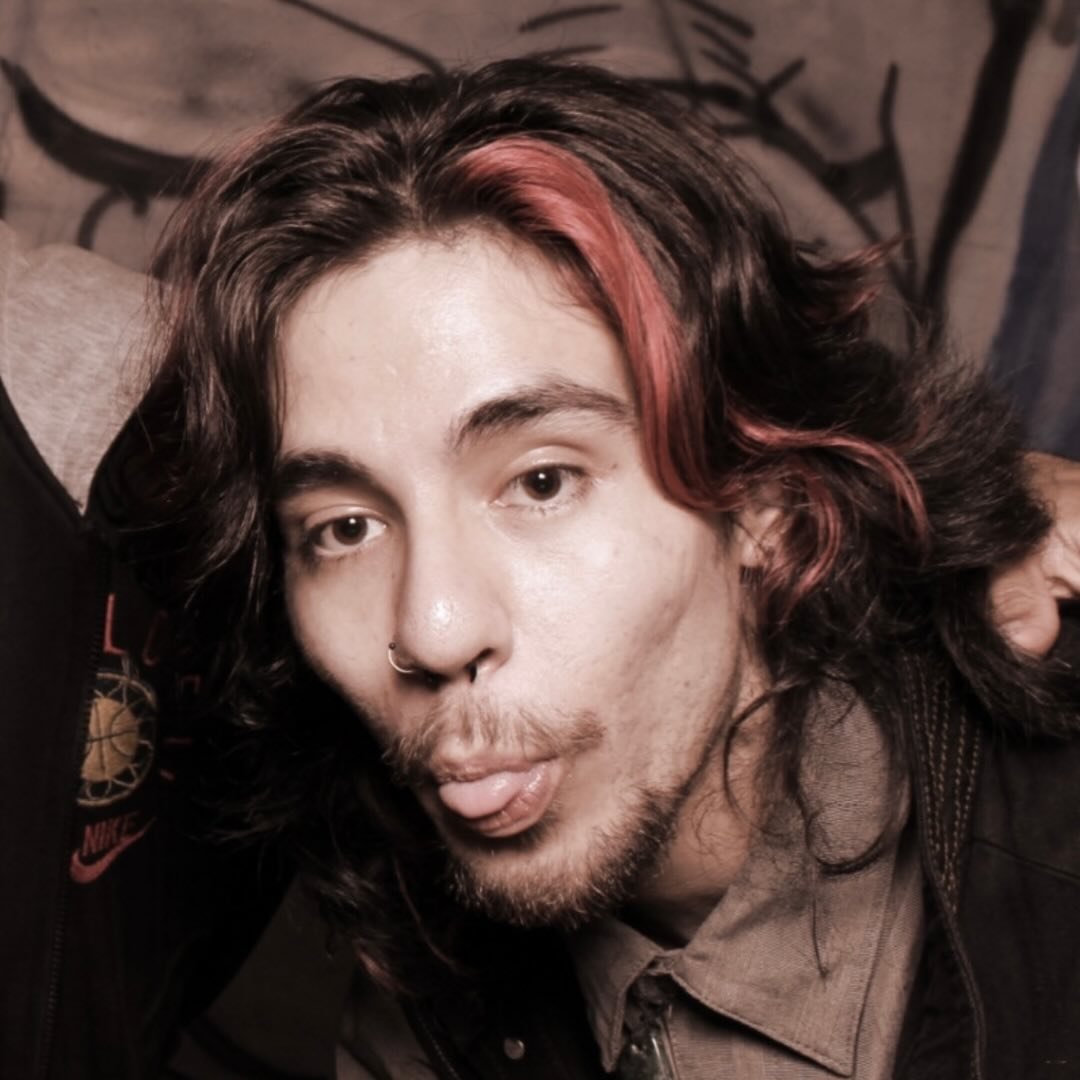

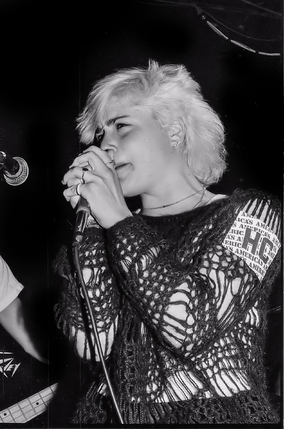

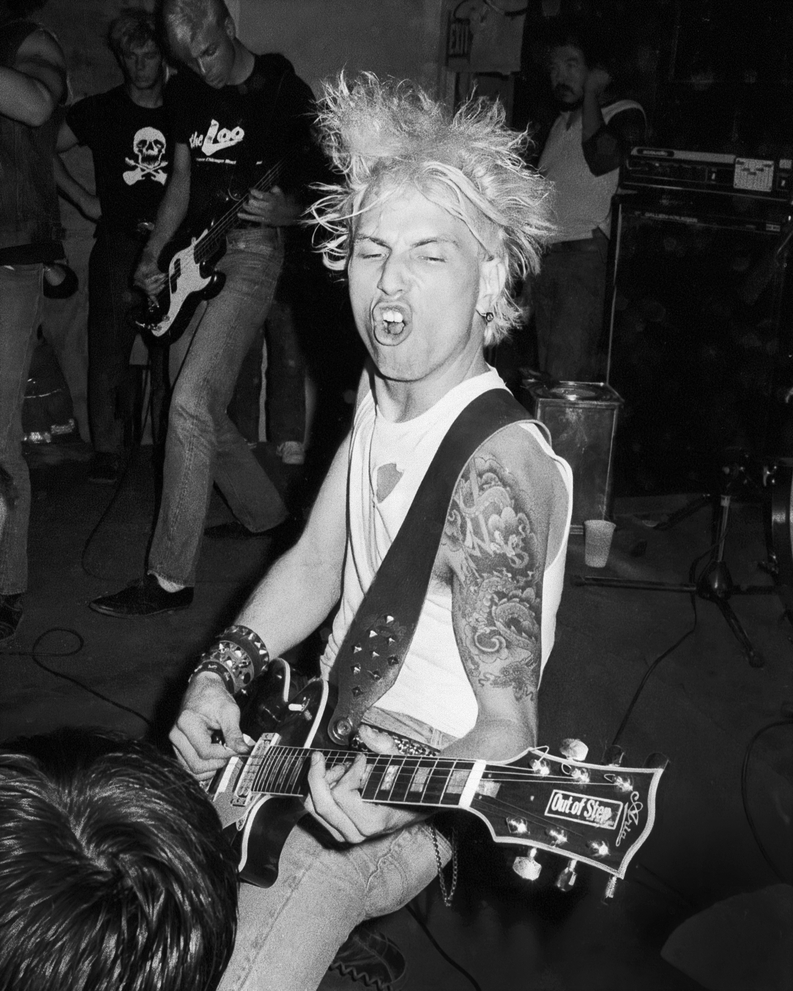

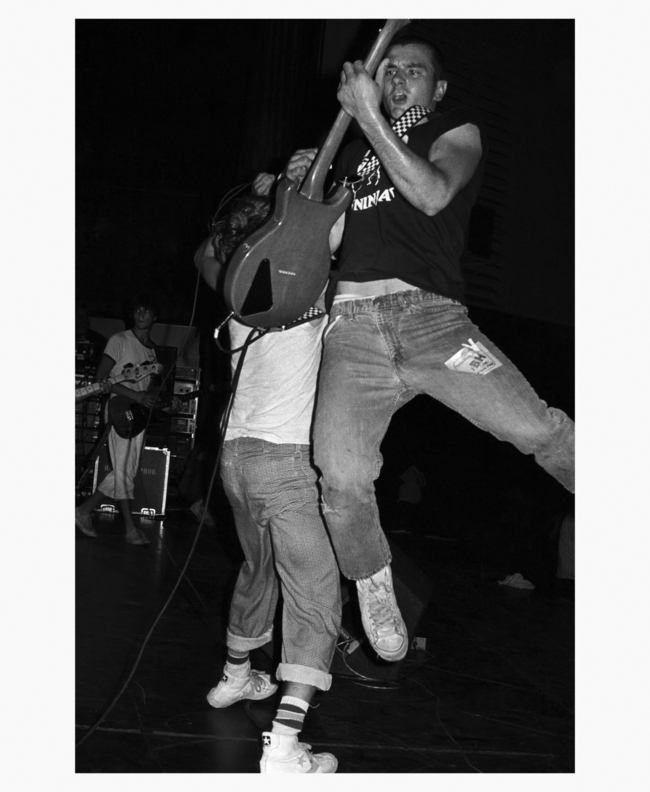

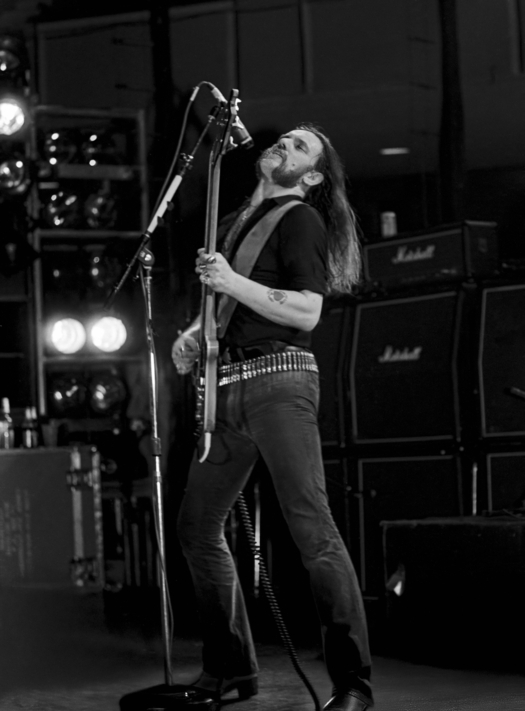

Featuring 12 photos of those we loved & lost. May all subjects rest in peace.

From the beginning, I knew I was witnessing something special. I didn’t just snap pictures for fun, I understood I was documenting a pivotal moment in music history. Something raw, real, and culturally significant. I did it for the fans; the kids packed into grimy clubs, the ones who lived for the music but didn’t always have a way to remember it. These weren’t polished press shots, they were for those who were there and those who couldn’t be. I wanted to capture the spirit of the music as it truly was, because I believed it mattered then and always will.

Within any subculture — punk, metal, DIY scenes — there comes a time when the people who were there, who lived it, won’t be around to tell the stories. And that’s exactly why documentation is vital. These movements often exist outside the mainstream; they aren’t preserved by institutions or broadcast on the nightly news. If no one captures them, they disappear.

I think my photography helps preserve the reality of its era – not just the legends, but the energy, sweat, chaos, and DIY spirit. It contributes to how punk and metal are remembered as movements, not just musical genres.

When I put out my first books of archives, In the Pit and later Shot in the Dark, the response was bigger than I expected. People appreciated that the photos weren’t staged. They were in it — you could feel the bass, the beer, the torn fishnets. Critics have called them raw, honest, and historically important. Fans say it brings them back. Younger folks say it helps them understand what these events were really like. That’s the best I could hope for: that my work resonates across time. Not just with those who were there, but with those who wish they had been.

I actually studied biology in college. Photography wasn’t my major — it was a side hustle and a passion. I worked at a camera store to pay for school, which kept me surrounded by gear, film, & photographers. That hands-on environment sharpened my technical skills in a way the classroom never could. I was constantly learning about cameras, light, & process, then applying it in real time at shows on the weekends.

Then there was Mystic Records… Working for them was a whole different kind of education, the kind you can’t get from college. I was suddenly immersed in the business side of punk: album layouts, promo shots, dealing with unpredictable bands, and an even more unpredictable/divisive label owner. It taught me how to work fast, be resourceful, and navigate the controlled chaos of the scene. That experience gave me a front-row seat to how independent music actually functions — how fragile yet fierce it really is.

It was important to be there — to stand in the pit, camera in hand, and bear witness. Not just for myself, but for the bands, the fans, and the culture as a whole. The photos I took weren’t just snapshots; they became evidence that it all happened. That it mattered. That there was a movement driven by raw energy, rebellion, and community.

Archiving these moments ensures the spirit of the scene outlives the people who created it. It gives future generations something to connect to, something to study, and something to feel inspired by. Without that, everything punk stood for could vanish like it never existed. I didn’t want that. So I made sure I was there, camera ready, preserving what others might’ve overlooked or forgotten.

Moving to Seattle after college was a shift; I had already built a strong network in L.A. People knew me, I had access, and I was part of a scene that felt like home. Coming into a new city, even one with a thriving music culture, I didn’t have the same connections and had to start from scratch.

I’ve always believed that if you show up consistently, respectfully, and with real intent, people take notice. It took time, but eventually I found like-minded individuals from musicians, artists, zinesters, and photographers who were just as passionate about the scene as I was. Seattle’s community had its own rhythm & style, but as long as I had my camera, I was part of the story, even if it took a while to find my chapter in a new city.

Eventually I started writing for punk fanzines like Maximum Rock’n’roll and We Got Power, which gave me a whole different lens to look through. As a photographer, I was capturing energy and chaos in the moment. But when I started conducting interviews and writing scene reports, I had to slow down and listen. It pulled me deeper into the lives behind the music; the motivations, struggles, and philosophies that didn’t always come through on stage or in a photo.

It made me realize that scenes aren’t just built on sound, but on relationships, values, and shared experiences. Interviewing bands shifted them from being subjects in my frame to people with layered stories. I saw how much effort and sacrifice went into touring, recording, surviving — how much of it was done purely out of love for the music and the community.

Writing also gave me a voice beyond the visual. I could contextualize what I was seeing, call out what was happening, and contribute to the documentation of a culture that didn’t have mainstream visibility. It deepened my connection to the scene, not just as an artist, but as someone who was part of preserving and shaping its narrative.

Some of the most meaningful relationships in my life were born from shared moments in dimly lit clubs, on sticky floors, and through the lens of my camera. A few people I met just once or twice, but the interaction stuck. Others like Jello Biafra and Edward Colver became longtime friends. It’s wild to think how many of those friendships started with a snapshot and turned into decades of mutual respect and shared history.

There’s also a kind of unspoken loyalty in those connections. We came up together in a scene that didn’t always get recognition or support from the outside, so the bonds run deep.

Being a woman with a camera in the early punk and metal scenes wasn’t easy. Most people didn’t take me seriously at first. I was assumed to be someone’s girlfriend, a groupie, or just there to hang out. I had to fight for access, respect, and basic safety in environments that weren’t exactly welcoming to women. I learned quickly to stand my ground, know my gear, and let the work speak for itself.

I didn’t want to be the exception, I wanted to make space. I wanted other women to see that they could be behind the lens, telling the stories, shaping the narrative. There weren’t many of us doing that back then, so just being there, holding my camera like I belonged, was an act of resistance. It challenged the idea of who gets to document culture and whose perspective counts.

Stepping into portraiture and other forms of photography was part of my growth; I wanted to challenge myself, explore new techniques, and work in different environments. It gave me fresh eyes and a deeper appreciation for light, composition, and human expression. But no matter where I went creatively, music always pulled me back. There’s just something about the energy, unpredictability, and intimacy of documenting live events and the culture around them that nothing else quite touches.

Returning to the music world felt like returning home with more tools, more insight, and even more reverence for the culture I came from. The roots didn’t just hold – they grew deeper.

The best way to support me — and others doing this kind of work — is to value it. That means buying prints, books, zines, not just liking a photo online and moving on. Share the work, credit the artists, and understand that documentation is labor, not just nostalgia. Behind every image is someone who hauled gear, got kicked in the pit, lost sleep, and kept showing up because they believed the moment was worth capturing.

Support also means showing up for independent art in general. Go to gallery shows, donate to archives, follow and promote lesser-known voices.

Ask questions & stay curious. The more you dig into the stories behind the image, the more you’re keeping that history alive.

-Alison Braun for Dead Relatives.