HASSAN (Vox): According to Europe, I’m a “person of color,” “Pakistani,” “Muslim,” “brown male” and various other identities that mean nothing to me. Meanwhile in Pakistan, I had other identities to contend with regarding the linguistic backgrounds in my family, the province I lived in, religious sects…

But really, I could care less about these things. I’ve always identified as an outsider and an outcast. Thus every sort of identity feels like a burden on me. What do these words mean anyway? Brown, white? What does being Punjabi or Pashtun mean either? I didn’t feel brown in Pakistan, and none of my Pakistani identities mean anything here in Germany. They’re just colonial stereotypes using outdated methodologies that’s been superimposed on the rest of the world. There are more fluid and interesting ways to understand the diversity of human cultures and groups that exist… Let’s deconstruct this sh*t.

Like a myriad of Sufi poets from my region have expressed for centuries – identifying as a human being is the most important thing.

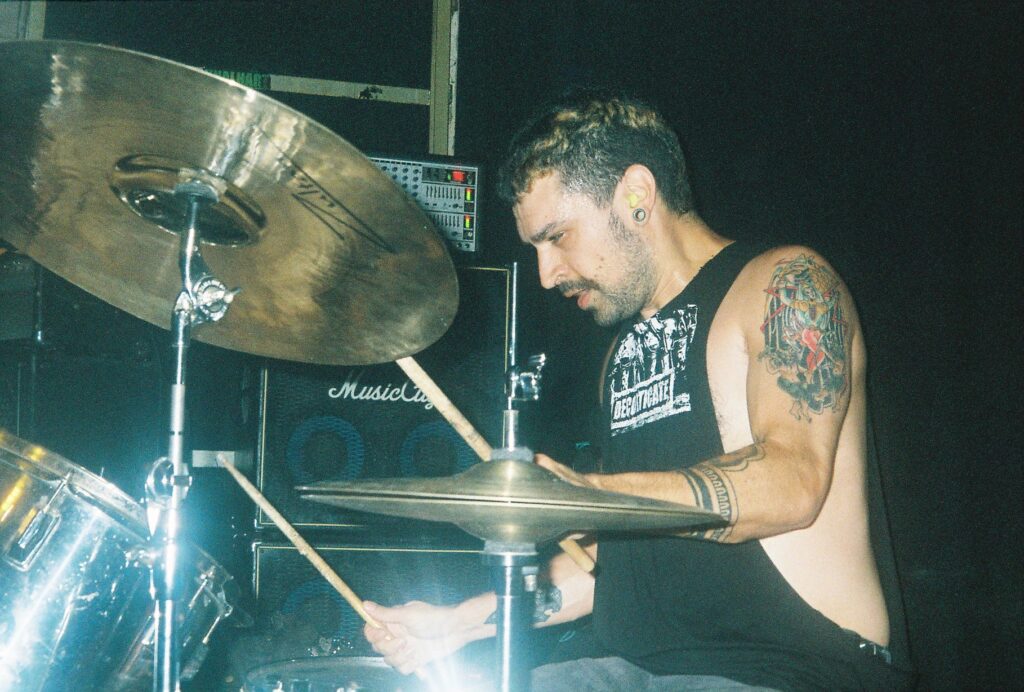

STEVE (Drums): I represent no one but myself, an Anglo-Iranian postgraduate Linguistics student who wanted to get out of the UK for a while, attempting to construct an oasis of peace and calm amidst the chaos and despair of the modern world.

My dad was from the slums of Hockley in Birmingham UK, got into oil machinery engineering, and lived and worked in Iran for a while before the revolution. Many foreign workers were living over there with their families and relations with the ‘West’ were open and friendly. My mom is descended from Bakhtiari and Qashqai nomads in the Southwest.

Just after the turn of the 20th century, it was in Bakhtiari territory that prospectors working on behalf of British aristocrat William Knox D’Arcy first struck oil, leading to the creation of the Anglo-Persian oil company (that would later become British Petroleum). This was the starting point of several decades of internal and external British f*ckery in Iran. The Brits had to cut a deal with the Bakthiari chiefs (Khans) for permission to start drilling, which pissed off the Shah as it bypassed his authority and the central government in Tehran, which tribal communities often didn’t fully recognize anyway. The Bakhtiaris were key players in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1909 which sought to limit the absolute powers of the Shah and modernize Iran’s political structure, marching to Tehran and forcing the abdication of the Qajar ruler Mohammad Ali Shah in favour of his son. With all that in mind, I feel like my very existence on this planet is tied to oil and a sort of cultural antagonism.

My mom fled to Sweden in 1984 during the Iran-Iraq war, so I was born in Stockholm and spent my first few years of life there. I was raised bilingual between English and Farsi. My mom worked all year round, and my Dad lived abroad until his death, so during the school holidays I’d spend entire days at home with too much time on my hands. One day I opened the insert of my Tony Hawk Pro Skater games out of curiosity and saw all these band names in the music credits – Bad Religion, Lagwagon, Millencolin, Swingin’ Utters, Dead Kennedys, Suicidal Tendencies, Consumed… I looked them up online and kept seeing this word ‘punk’ everywhere. I had seen TV documentaries on punk where it was associated with uncouth, violent types with mohicans and chains, erroneously spoken of as a thing of the past. It was not something I imagined myself getting into, but I was wrong as it turns out.

I was pleasantly surprised that anti-racism was often a central theme to the music. The availability of the Epitaph ‘Punk-O-Rama’ compilations in mainstream record shops maintained my interest, and around the same time there was a sizeable home-grown skate and ska-punk scene in the UK. Age restrictions due to alcohol licensing laws were a real barrier to younger music fans wanting to watch bands as most independent gigs would take place in pubs, though there was a well-known club in Birmingham called Edward’s No. 8 (Eddie’s for short) that admitted kids the wrong side of 18 years old. It’s where I first saw Discharge at 14. It burned down in suspicious circumstances in 2006, unfortunately.

A large chunk of my late teens and 20s were spent travelling to other cities for gigs and fests (Leeds, Nottingham and London mostly), meeting likeminded people, and generally having fun. I think beyond the music itself and the accompanying political outlook, it was the sense of community that made it all seem so irresistible to me, and what I suppose I’d call a ‘fleeting sense of freedom and tolerance’ that was hard to come by in other areas of life. You could get shit off your chest and feel listened to; people seemed to genuinely care about each other. There was also a general irreverence and sarcastic sense of humour I found very appealing.

For quite a long time, punk was the only place I felt like I really ‘belonged’; everything else just felt boring, oppressive, or otherwise uninteresting. I don’t know to what extent that is still true for me these days, but it’s become all I know in a way – for as long as I can remember there was never any question of not being into this music and involved in some way.

H: I speak Urdu because I was raised on it, and Punjabi because it’s the main language of the province I’m from. Urdu is the national language in Pakistan, however Pakistan is an incredibly multilingual country that has languages from the Indo-Aryan, Iranian, Tibetan, Dravidian branches, even some language isolates. Urdu was spoken by a minority of people in 1947 when Pakistan was made, it’s actually native to North-Central India, but due to it being spoken and understood by the business and military classes, and having an entirely constructed “Islamicness” (it actually was spoken originally by both Hindus and Muslims), it became the official language of Pakistan.

Unfortunately, unlike neighbouring India where every state can choose it’s own official language, our local languages are not really promoted by the country. Urdu creeps more and more as a first language. It’s not uncommon that in a big city like Lahore, a Punjabi teacher, or your Punjabi parents, would discourage their Punjabi students from speaking in Punjabi, for example. Which I find entirely insane. There are likely worse experiences for other ethnolinguistic groups in the country, Punjabis are still a privileged majority.

Due to this I actually lost fluency in Punjabi despite understanding it completely. When I came to Germany I was faced with several questions about identity and the idea of roots, familiarity… I realized that despite Punjabi being an incredible language, the entire Urdu culture of Pakistan is constructed at the expense of our real indigenous languages. If you’ve heard about International Mother Language Day that’s celebrated by the UN, well, Pakistan is responsible because we killed Bengali speakers in the former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh after they fought back against a brutal genocide from Pakistan).

I realized one day when reading Wikipedia in Punjabi how much easier it is for me to comprehend the information compared to Urdu Wikipedia. I’d feel the same reading poetry and prose. When I realized Punjabi provides me metaphors and imagery that are directly tied to where I have roamed most of my life, Urdu literally started to feel foreign. Punjabi feels incredibly intimate to me, especially the local Lahori Majhi dialect where I’m from. So I worked on perfecting it properly, and want to learn other dialects of Punjabi as well.

S: Hassan came up with the name while recording the EP. It means ‘chain’ in both Hindi, Urdu, and Persian (Farsi), as well as quite a few other languages in the region. In Persian it can refer to a chain as the physical object and is also used in modifying nouns like ‘chain store’ and ‘serial killer’.

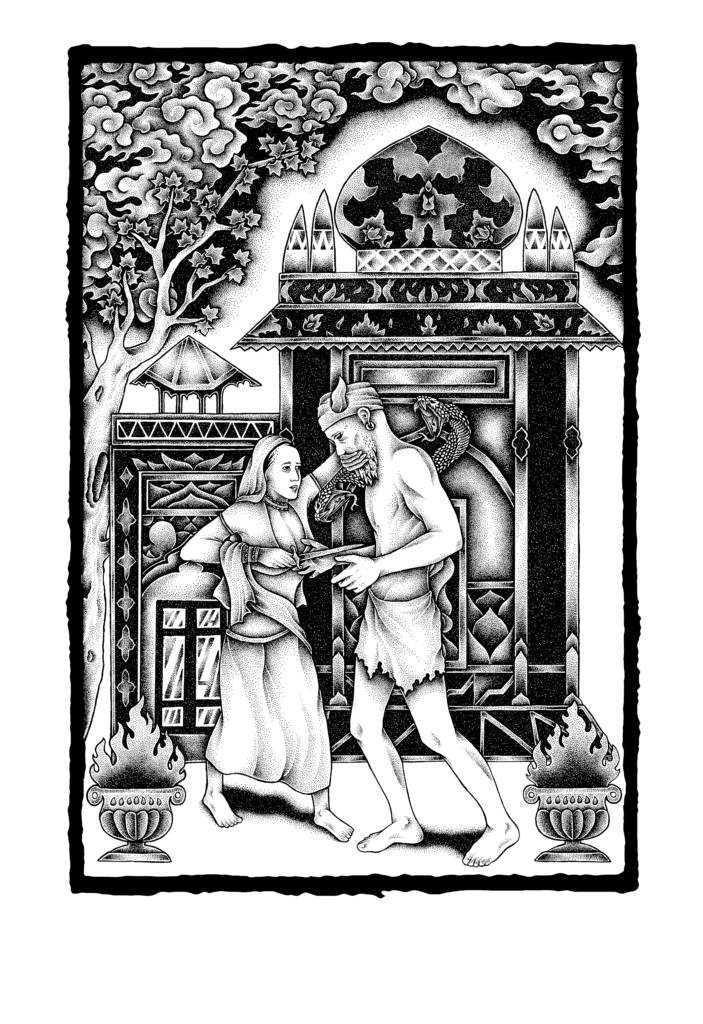

H: In Pakistan there’s a ritual called Zanjeer Zani where you hit yourself with chains that have blades attached to them. It’s in remembrance of the martyrdom of Hussain, who was fighting against the tyrannical caliph of that time. There’s other connotations to the name Zanjeer too that could refer to a Sufistic outlook towards humility. But mostly it just sounds cool. I think it’s a no-brainer that a punk/metal band singing in our languages should be called Zanjeer.

S: There are multiple metaphors that go along with the name that we didn’t necessarily have in mind at the time; chains being tools of detention, oppression and restraint, but also as parts of weapons, and how lots of small interlinking pieces can make up something much more powerful as a whole. Also in the sense of a ‘chain reaction’, how one small, seemingly insignificant event can be the catalyst for a much grander happening later on.

H: Me and Steve split up the lyrics. For my side, the Urdu and Punjabi lyrics are a bit direct and in-your-face, expressed in the same way I would when ranting at a naan shop or chai stall in Lahore over Capstan cigarettes. On the previous EP I wrote mainly about Pakistan and also some experiences about my recent migration. If you read the lyrics to ‘Ijtemayi Bemaari’ (Societal Illness) or ‘Hamdullah’ (Praise be to God) you’ll see what I mean. On our upcoming releases I’m a bit more focused on experiences in Germany, since I’ve been here for 5 years now and Pakistan feels more and more like a distant memory.

S: I wrote the lyrics to ‘Nakhair’ (No Way) and ‘Na un Moghe, Na Hala’ (Not Then, Not Now) in Persian, as all previous attempts to write lyrics in English have made me cringe hard. ‘Nakhair’ is basically someone lamenting a stagnant and deteriorating socio-political-economic situation, observing the toll it takes on the environment as well as their own health and wellbeing, asking rhetorically how much longer they will have to wait before seeing any improvement. It’s inspired by the UK and Iran equally but could be applicable to anywhere. ‘Na Un Moghe, Na Hala’ is a criticism of colonisation and the erasure of local identities, inspired by the solidarity between the Mapuche and Kurdish movements I saw while living in Chile between 2015-2016, and again could be applicable to anywhere: Kashmir, Kanaky, Palestine, West Papua, East Turkestan… The list goes on.

Compared to other places I’ve found punk, I’d say there are more resources available in Germany due to its favourable economic outlook. Touring bands can usually expect a decent meal, a comfortable place to sleep, and as many drinks as they want without anyone having to foot the bill. A lot of spaces are collective and volunteer-run, compared to Chile, for example, where I learned that bands usually don’t get paid for travel expenses and most gigs are to raise money for various causes though ‘soli-gigs.’ These also happen in Germany.

H: Moving from Pakistan to here, this scene is great. I count my blessings every time I enter a rehearsal room, go to a show, or am given the opportunity to take the stage myself. There are political issues internally, but they’ll be sorted as more migrants storm the barricades of punk. I found the scenes in Belgium, Netherlands, and Poland great too, but honestly I’m easily impressed by everything punk related in Europe because I don’t have anything like this back home.

S: If you’re not fluent in German, you might feel left out as not all Germans are comfortable speaking English. There are also some idiosyncratic orthodoxies to the scene here I haven’t encountered elsewhere; male performers removing their shirts on stage is frowned upon and many (but thankfully not all!) German punks have some, er, interesting takes on the Palestinian question due to guilt from their past. (If you’re not familiar, look up who the ‘antideutsch’ are, it’s totally bonkers.)

H: Final thoughts: don’t collaborate with pigs, read up & learn before opening your mouth, and don’t defend sh*tty regimes just because they are against the USA. Tell your homies you love them.

S: To anyone who took the time to read this, always be true to yourself and don’t let the bast*rds grind you down.