BILL DUNLEAVY, Photographer & Director of SUPERCHIEF GALLERY:

To me, the art gallery world always represented something very elitist and bougie. What we started doing with Superchief was bringing a lot of working-class people into the fold, because everybody we created with were just kids from the gutter trying to make it happen like us.

My dad was a slot machine technician in Atlantic City. He did a six-month job on a gambling cruise ship when I was a kid, traveled all over the world and took a camera with him. When he got back he showed me so many crazy pictures that I couldn’t believe it was his life.

He gave me his camera and a book on how to use it…

I started out documenting troublemaking with my friends, for the most part. When I got a little older I started taking photos at West Philly Anarchist punk shows with bands like Choking Victim, Leftover Crack, and World Inferno Friendship Society. Then I did the same around New York, New Brunswick, and New Jersey. The Internet was barely coming around. I started to get into photography as an art form through people’s photo blogs I had met through the punk scene.

This is all pre-social media, so you more or less had to find out about people. And once you got to meet someone or had a friend show you their work, you could subscribe to their blog and keep up with their journal of their life.

I started going to noise & punk shows and kind of became a bad student towards the end of high school, after being a smart kid my whole life – a really rebellious one that was interested in psychedelic culture, getting into crazy adventures every weekend, thinking he was too cool for school.

I finished my high school era crashing on friends’ couches, barely skating by. At that time, I was reading into the history of anarchist collectives & alternative art movements, really bent on trainhopping and squatting. I was trying to make it in any other way than what society had intended for me.

I moved to Montreal following a girl, ran out of money, then moved back to the east coast to this punk house in Bed Stuy, Brooklyn, off Gates and Malcolm X. That house was pretty chaotic. We would get nickel bags of weed and blunt wraps every day, sharing bags of chips with Arizona iced teas. Subsided off of that for a long time.

Soon, I got a job at the B&H camera store in Midtown Manhattan. I was able to work around selling cameras, met a lot of photographers, and started taking my own photography seriously.

I saved up some money and heard about a photojournalism residency program in Mexico City taught by war photographers from Magnum and VII (Seven), two big agencies. These were people who traveled the world to document left-wing struggles against imperialism.

I applied, got accepted, and asked for a month off from work for the class. They said no, even if it was for photography, so I quit and began a Greyhound bus trip down to Mexico City from New York with no real end goal. I hung out with the friends I knew along the way. My first stop was Baltimore, where I had a good friend from the punk scene in New York who went to art school at MICA. I visited a collective called Castle Unicorn Island, in the former home of Wham City – very welcoming, freaky, and brought a lot of adjacent communities together. I had never really seen a group of people live in a warehouse and run an art collective to such an inspiring degree, and I kind of knew right then my future was probably going to be the closest thing I could find to that.

It wasn’t until I landed in Mexico City at midnight that I realized I didn’t really know anything about the culture; I didn’t even really speak Spanish. I tried walking out of the airport, and the workers pulled me back, called a cab to keep me safe because they knew I’d be a target. The class the next morning was like a crash course. It was all these international conflict photographers teaching students the basics of professional photojournalism.

They told us that the first assignment for a photojournalist in any situation is to hit the streets and find a subject, then pretty much just set us loose. I ran into a group of street punks in The Zocalo that were handing out a socialist newspaper. I asked them in my broken Spanish if I could take pictures, they thought I was funny and random as f*ck: Who the hell is this güero from New York? But I paid for their beer after and they invited me back to their squat.

I began photographing these kids regularly and did a whole photo series on them. The photojournalism residency ended, and I kept doing the story. I got a job teaching English which helped me improve my Spanish. I was posting everything on my blog, and one of my now best friends, Daniel Hernandez, was in Mexico City writing a book about subculture in Mexico. He saw the access that I was getting with these punks/skins and contacted me to try to get in with them for his book.

I remember questioning and grilling him… Turned out he was a super expert on Mexico, a professional journalist on a mission. Thank God I met him because he started to teach me a lot of history and Mexico’s current politics. This was during the famous emo versus punk riots in the Insurgentes Metro. I stayed down there for the better part of a year.

I was looking for alternative publications to submit my photos to when I heard about this magazine called Chief in New York. It seemed raw and crazy and on the level, so I submitted the photos and returned to New York to meet with Ed Zipco, my current business partner, who was running Chief magazine. He asked me to intern, and I got my photos in the next issue. Then, right after that, his business partner quit. It ended up being the last-ever release of Chief magazine. Ed and I hung out for a few months, and then he proposed that we start a new magazine together, called… Superchief.

I remember hating the name, but he really wanted to do a Mario Brothers, Super Mario Brothers, sort of thing. He asked if I had a better one, and I couldn’t think of anything, so I rolled with it.

We started Superchief Magazine in 2010; it was a continuation of the blog era more than a magazine. We published articles, interviews with artists, crazy editorials, and photography on our website. I remember being 23 years old, just publishing whatever the hell I wanted.

During those first magazine years, I was very interested in photojournalism and started pursuing that as a goal for my life. I was covering a lot of radical protesting in New York, like the student occupations at The New School and NYU.

One group of anarchists would do these riot events, trying to pull a bunch of people to show up in one place in costume, so they could blend in and not get caught f*cking with the system. One time, they put flyers all over New Yor,k trying to appeal to hipsters and normies like, It’s a cat-themed dance party! You gotta be there.

The event was called Cat-astrophe…

All these motherf*ckers dressed like cats showed up and a parade started. As everyone’s walking through the city, the undercovers smashed windows & set fire to trash cans, spray painting corporate businesses. Of course, the cops reacted, but then they’d just rejoin the confused ones in the parade, and no one would be able to track them down because they’re all dressed the same.

The second one I photographed was called Panda-monium – as you might be able to guess, that one was panda-themed. Then Occupy Wall Street happened and I went all in. It was America’s first taste of wealth redistribution.

I wasn’t taking Superchief as a magazine super seriously; I had to go to work and live my life, but it was a lot of fun. We used to recruit off Craigslist and whichever random-ass interns showed up that were cool, we’d keep. But we loved to throw ghetto late-night afterparties with the people we published, they were getting pretty big towards the end of that era.

After a couple of years, someone offered us a space to use in Williamsburg to host an event, kind of a nicer neighborhood. We decided to present an art show because that would be a more validating thing for the neighbors to see than just a party. We brought in Lofty305 and Poshgod, and I’d say that first show was the birth of Superchief Gallery. Once that happened, we never really looked back – Ed and I started curating a lot of shows, and soon we were asked to put together weekly shows in a gallery room attached to a struggling bar on the Lower East Side. We got in so much trouble there <haha>.

I think seeing the difference between the type of art shows we were hosting and the types that were the norm made me realize what we were doing was something special. It was really cool to put people on a pedestal who I felt like were being ignored by the art establishment.

There was an expiration date on the bar, so I started saving up all my money for whatever came next. We ended up teaming with some people I knew from Baltimore to pool our money together and move to LA. I remember looking at warehouses every day while living on a hotel floor in Torrance, the four of us sharing one room.

We found a cheap warehouse we liked with a landlord who didn’t really care what we did. It was on Kohler St. between 7th and 8th near Skid Row. We found some contractors at Home Depot and put in a shower, some bathrooms, and ten studios we drywalled ourselves. Then we flew back to New York, loaded a U-Haul with all of our friends’ art, and drove across the country back to LA to host our first show there in 2014 with Swoon, Death Traitors, Mike Diana, and everybody we had gotten down with our roster in New York.

We lived in the warehouse, throwing shows and parties and renting out the studios to cover the rent. It was a crazy time that went on for seven years. I started out pretty experimental in the early days. I would say 2-3 years in is when I began developing the real skills to run a good art gallery.

The first time we had a really successful event was when we threw Parker Day’s first photography show; it was a sellout. Then we debuted another artist, Sarah Sitkin, who does incredible silicone work. Yu Maeda from Japan is another. We also debuted Sick Kid when he was 19 years old, another sold-out gig.

There were 55 shows that I did in seven years, and a lot of them were huge bangers. We became well-known for doing really immersive, extreme build-outs because we were free to do whatever we wanted in there. Once the ball got rolling, we started getting taken seriously in the art world – Juxtapoz Magazine jumped on us and started sponsoring our shows, inviting us to be a part of the Juxtapoz Clubhouse in Miami Art Basel. That was a ton of exposure. I rode that wave for a good many years in that old spot.

Right when things were going great, up to 2020, our neighbors two doors down from us had an accident. They were illegally making hash oil with butane extraction, which caused a giant explosion that blew the building up. It killed two people in their spot, injured way more, and blew a corner of our building clean off.

Our building was condemned and we had 10 people pretty much living at the gallery at that point, sneaking in and out of a chemically burned building that none of us were supposed to be in, because we had nowhere else to go. And three days into moving what was left into storage units, all this news starts popping up about the coronavirus.

With nowhere to go and not wanting to ask to couch surf during a pandemic, I hit up a friend who owns some property out in Death Valley, packed up whatever didn’t fit in storage, and drove out to this house in the middle of nowhere. I was with my then-girlfriend and a close friend of ours.

Two weeks turned into two months. We were out in the desert, going crazy and wondering if society was on the brink of collapse, kind of scared and uncertain.

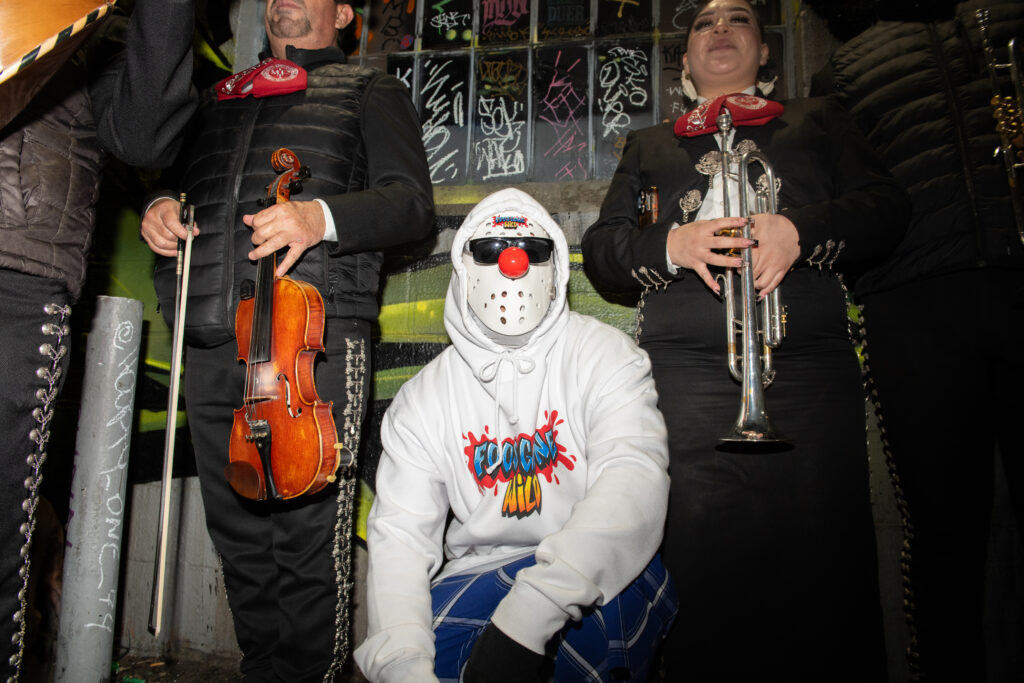

We had to move around and I rode out the pandemic in another artist warehouse spot in South Central. After the Dead City Punx show in Frog Town, I knew the pandemic was not as bad as people thought; it was only a matter of time before society returned to normal. So I started on the warehouse hunt once again.

I was forced out of the game at the height of my success and momentum, I had to ring it back.

When we moved into our current location on Los Angeles Street, it was a little rocky, trying to figure out the vision for managing everything. I wanted to come with a more professional approach this time.

I’m really proud of the work I’ve been able to do with Superchief post-pandemic. It’s leveled me up in so many ways professionally and as a human being – it’s continuously a challenge, but I think that’s where I thrive.

I’m proud of my life and the weird twists and turns that have led me to where I am right now, for all the respect I’ve gotten over the years and for falling in love with the LA scene. I’m even more proud of all the different subcultures that I’ve represented through the gallery in this city.

-Bill Dunleavy for Dead Relatives.